Unite The World: Combat Model Highlights

Eventually, countries have to fight for their place. Rapid technological change has a tendency to drive conflict. If you want to simulate geopolitics, the warfare has to make sense.

Introduction

Truth be told, Unite The World first began as a thought experiment in how to make a better wargame. Born in 1983, I’m at just the right age to have started playing computer games in the 1990s, when simulations were a lot more common than they are today.

The dramatic decrease in the cost of computing power during the 1990s allowed for a tremendous amount of experimentation in digital games and simulations. With the Cold War only just ended, and potential for a resurgent Moscow taking revenge for losing much of its empire as the USSR fell fresh in mind, digital wargaming took off.

I’m actually not one for nostalgia - a lot of what was produced then was naturally terrible. And as irritating as a lot of technology trends have become in the era of the dominance of the phone, most folks today don’t have to fight to get a program’s settings just right in MS-DOS or Windows 3.1 to work. Oh, Config.sys and Autoexec.bat, how I don’t miss fiddling with you!

Yet titles like Steel Panthers, Janes Navy Fighters, Falcon, Harpoon, and even more casual offerings like SSI’s Panzer General series offered simple, straightforward gameplay that made professional matters accessible even to a teenager growing up in rural northern California. I’d even say that the broader public understanding of military affairs in the immediate post-Cold War era helped prevent the collapse of the USSR from immediately going the way Putin’s ruscist nightmare eventually did.

The end of the Cold War meant a substantial reduction in the number of people directly serving in uniform across the richer parts of the world. A side effect has been a slow reduction in the impact that people with military experience have on culture. As military experience became less universal, so did a broader awareness of its true essence. Warfare slowly but surely became seen as a kind of catharsis, a metaphor shorn of its ancestral connection to life rhythms that have driven humanity for millennia.

A side effect has been a dangerous deterioration in the quality of military science - and probably doctrine, too. Military readiness and effectiveness are certain to be impacted. The reason is so obvious it’s easy to overlook: there aren’t enough people in the population with a sufficient degree of technical knowledge to call BS when appropriate.

It is very easy for a great idea to take on a life of its own and escape the chains of common sense. People who have to implement ideas and plans always have the final say in whether they are feasible. Much harm is done when those far from the implementation either meddle in execution or demand the impossible against all advice.

Wargames have largely stagnated as a function of catering to a small niche market. That’s why I view it as essential to expand the genre to always incorporate economic and social factors in any title that looks at broad scale movements, anything above the tactical level. A wargame is a dynamic system that allows for creative experimentation, one which can reflect the real world is a priceless training and research instrument.

So: this post will focus exclusively on that component of Unite The World. It won’t dive into hard numbers, particularly because these will be the subject of intense experimentation when I can get a prototype built. Instead, I’ll explain from a user’s point of view how the process of building and using combat power works.

How to Conquer

In a conflict, the fundamental objective is to neutralize enough of the enemy’s combat power in a target province to allow friendly forces to seize control of vital points. This is done by having these locations fall within the boundaries of a deployed ground unit for an extended period of time.

To avoid forcing users to cope with dozens or hundreds of detached units, military forces will be represented as amoeba-like blobs that spread out across the terrain. Their size will be a function of the number of sub-units within as well as posture settings chosen by the player from a list.

Each blob will function as a distinct organism that manages its own affairs - attack, defense, even scouting is automated. In the real world, the person who tells a division or corps to go someplace and fight for something has practically no control over anything that happens next. Institutional wheels are set in motion across the chain of command, and the national level leader who attempts to meddle in the affairs of a single team or squad among hundreds or thousands is a fool.

Most modern grand strategy games will give the player tremendous amount of control over fine aspects of their forces, but this is deceptive, ultimately tweaking a few cosmetic values in a deeper algorithm. That’s fun and all, but can quickly become time-consuming in a world-spanning game unless deployed formations are ridiculously large.

A simulation generates complexity through careful limits on localized control, allowing near-infinite high-level variation. Like a real world national leader, players in Unite The World will get to say where and when their forces fight, what equipment they have, and how aggressive they are, but factors like training, logistics, and the enemy’s capabilities to determine the outcome of a given battle.

This makes the size of the blobs placed on the map by the player a function of the terrain and their own preferences. Someone who is content to have a big army that grinds forward into a target province can have that, and the more tactically-minded player who enjoys the challenge of optimizing their plans on the fly can have their fun too. Naturally, different strategies can also compete and be systematically tested.

Most of the skill involved in controlling battlefield formations will derive from understanding how their capabilities can be best applied. One that has a lot of artillery, for example, will aim to stay well behind the front and highly dispersed. An assault force that intends to rush into enemy territory on the other hand may concentrate into a tight fist immediately prior to moving forward.

Players will be able to select from a list of simple postures, each corresponding to a different default behavior and ability to respond to certain threats. When set to hold and defend an area, the blob will move into a tight oval and fire at anything in range. Told to advance, it will form a spear shape. An elastic defense which entails allowing the enemy to push forward before snapping back in a counterattack will form a bend. And so on. This cartoon isn’t great, but should get the point across.

Within each combat cell, the assigned components are assumed to be distributed in accordance with the selected posture. One with a mix of infantry, tanks, and artillery will treat them as if the artillery is in a portion of the cell behind the infantry and adjacent to or behind the tanks. Attacking a cell from the flank or rear will be especially damaging because more vulnerable “soft” targets cluster there.

Each combat round, all assigned units will contribute some number of shots that each inflict a certain amount of damage to a particular target type. Following classic wargame practices, every cell on the map will have attack and defense values for different weapons types (anti-tank, anti-infantry so on), with these being a function of the attributes of the units assigned. Each shot type will also be associated with different maximum, optimal, and close ranges, making the relative position of two hostile engaged units critical.

Each round, cells will fire at all targets in range, dividing their shots proportionally. The total amount of damage in each category is reduced by defense values and then further modified by the target unit’s speed, entrenchment, density, and range. The more tightly packed a cell is, the more focused and overwhelming its own strikes - but it is also more vulnerable. Hits assessed to have landed will be allocated to different parts of the cell, with sub-units in that space suffering proportionally to simulate the impact of attacks on a component of the organism, like tanks or artillery.

One of the major goals in any encounter between ground units is to cut off the enemy’s logistics. The logistics model is a critical component of the combat model, because to keep combat cells in the field requires a constant stream of supplies. Proximity to roads and railways is essential for large formations, as the effective supply throughput declines with distance from these and the ruggedness of the terrain. Transportation infrastructure is like like the circulatory system in the human body - if an artery, vein, or capillary network isn’t sufficient to sustain muscular activity in a region, bad things happen.

Any unit that receives insufficient supply will accumulate combat penalties that grow increasingly severe as the shortages worsen. The best way to defeat an enemy force is to surround it, cutting off sources of supply while keeping out of range of its weapons until it is effectively helpless. This, however, tends to require a lot of force, as a surrounded unit will attempt to break out with its remaining strength.

Simply bringing hostile terrain into range of some weapons will have an impact, but physically occupying important logistics nodes is always best. Not only does a unit with insufficient supply become weaker, morale will also drop, further worsening combat efficiency.

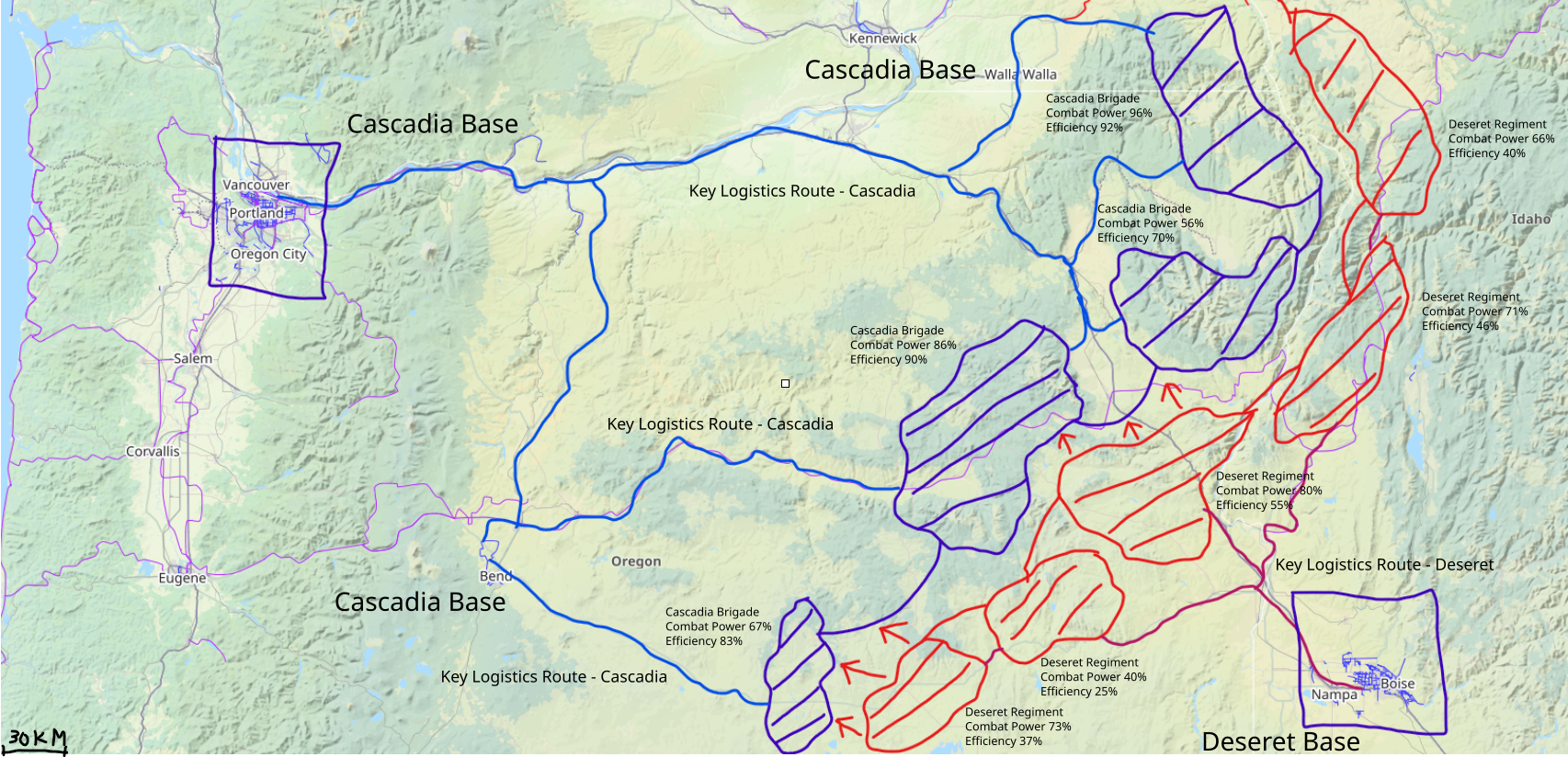

To model the impacts of supply, morale, and national policy, an efficiency factor is applied to all actions a combat unit takes. This effectively dilutes its power both on the attack and in the defense. This diagram gives a sense of what a battlefield might look like.

For the player, the main element of creative choice in operations rests in where to apply combat power to break through the enemy’s front and isolate vulnerable groupings. AI players will always strive to maintain a contiguous front, deploying reinforcements to stop threatened breakthroughs.

As a combat cell suffers damage, it will lose both combat power and efficiency. Past certain thresholds, a morale spiral can take hold that renders the unit impervious to command. It will retreat towards its logistics base until damage stops accumulating. To prevent this, battered units have to be either rotated off the line or allowed to conduct a fighting withdrawal, one of the postures that can be selected.

Knowing what the AI is up to will always be a challenge, as persistent uncertainty about intelligence will be modeled as lack of detailed knowledge of the enemy’s full dispositions. The player will always be presented a range of values and apparent enemy concentration areas, but not the full outlines of the enemy’s combat cell unless a lot is invested in intelligence and surveillance. Instead of a fog of war that obscures the terrain or other details, instead players will cope with a haze of uncertainty, only statistically sure of the enemy’s dispositions. The AI will face the same limitations, so blinding it where possible will always be a wise choice.

The terrain of course remains the ultimate god of battle, determining how quickly combat forces move, how deeply they entrench, and the difficulty of sustaining supply. And two particular forms of terrain are as important as the ground: air and sea. While taking and holding a province requires ground forces, as technology brings the world closer support from the sky and water is indispensable.

For the most part, aerial and naval combat in Unite the World is very similar to fighting on the ground. In a sense, both are special cases of ground combat that require cells to return to base with some frequency, interrupting the continuity of operations. Although, to simplify management, it will be possible to establish a continuous presence, albeit with less impact on each combat round.

As with ground units, air and sea combat cells will be assigned an area, posture, and mission, say interdicting hostile forces or providing support for ground troops. They will have attack and defense values built up from the sub-units assigned. Unlike ground forces, which if pressed into contact form a fixed front where each seeks to displace the other, air and sea units can mix freely, those doing so assumed to be within visual range, where differences in sensors won’t matter.

The uncertainty levels surrounding air and sea units will be higher in most cases than their ground counterparts, with proximity to bases or special units with excellent surveillance capabilities playing a major role in combat efficiency. Also unlike ground units, air and sea forces will tend to hit with very few shots, but those that strike inflict tremendous damage that is applied using an algorithm to ships in the target cell. Where badly outnumbered ground forces can still conduct a fighting retreat, fleets in the sky or on the water tend to be forced to flee after suffering irreparable losses.

Another difference between ground and other units is that the latter deploy from a specific base and have self-contained logistics. To fully cut off their supplies, attacking the home base itself is necessary, and this tend to be no easy task, as ships and aircraft are at peak efficiency close to home.

Space forces are represented as a subclass of air units that become very important in the 21st century. They are not represented on the map, but modify values across a wide area. The electromagnetic domain is similarly abstracted as an area effect.

Because of their somewhat fragile nature, air and sea forces - at least until uncrewed variants become available in the 21st century - are best used for specific, time-defined missions. Sea forces are vital for securing trade lanes, which pass over the oceans much as roads do, linking ports. Hostile naval forces can savage these and damage economic growth forcing defensive patrols. Seizing provinces through amphibious assaults is also possible, especially where a port is available or can be constructed by engineers to establish a lasting maritime connection.

Air lanes also exist, and can sustain airborne operations, but aircraft are best used in close conjunction with ground and sea forces to boost their scouting and firepower. Another useful mission can be raids on high value targets; against enemy forces lacking sufficient anti-aircraft defenses the inability to shoot back can lead to lopsided results.

Both air and sea forces tend to be expensive - again, until drones are on the scene - and their deployment sends a message. But sometimes that’s exactly what diplomacy requires.

Developing Combat Power

Actually getting forces into the field and sustaining them in place is handled through a separate sub-system that links battlefield operations to other strategic decisions. A portion of each year’s tax revenues are allocated to defense by the player, and this income flow can sustain ready and reserve forces in certain quantities.

In the real world, defense budgeting is an incredibly complex affair. To avoid tedium, players will simply add forces of the desired size from a simple menu to a national inventory, each item increasing the annual budget outlay required. Ground troops will generally be purchased as complete battalions, air units as squadrons, and naval forces as flotillas.

Naturally, the budget space each element requires will scale with what it can do. The quality of what is available to the player will depend on their country’s income level, measured in in GDP per person. Deployed forces cost substantially more than those in garrison, but it is possible to deploy them as reserve formations at half the cost though at the penalty of two-thirds their paper strength.

Once in the national inventory, a purchased unit can be deployed as part of any combat cell. It is up to the player if the default cell they manage is large like a corps or smaller like a brigade, and battalion level control is possible. To reinforce a cell or base for ships or aircraft, the player will be able to quickly assign it from a screen accessed through any military facility on the map. Adding a new cell is done the same way. What matters is the quality and quantity of what’s inside.

For visual interest, it will be ideal if each cell contained representations of the forces contained within. Hardcore grognards can switch to NATO-standard icons if they prefer - having seen them so often to translate without a second thought, I’m one of those who prefers them to animations. But to each their own!

Likewise, more casual players not as interested in military affairs will be free to deploy big blobs full of different types of units without penalty, save perhaps a degree of in-the-moment flexibility that allows very skilled players an earned advantage through exploiting nuances of how terrain intersects with capabilities. But the underlying numbers game will be the same.

Ultimately, it will be entirely up to the player to fund and - at a high level - organize a force that suits their national policy. This arrangement ties the physical use of combat power closely to the country’s economic fortunes. Wars will additionally have a number of social impacts, some that ultimately feed back into unit morale and therefore combat efficiency. But as far as the geopolitical angle is concerned, it’s the ability to sustain enough income flow into the defense sector that determines how much combat power is available. On the flip side, all military expenditure is, in some sense, a wasteful drain on economic growth, since military production rarely adds value to some other part of the economy. It’s insurance, not capital.

By modeling warfare at a high level in this way, it’s possible to reveal the deeper connections that drive its course over the long term. As a wargame, Unite the World is meant to illustrate the dynamic evolution of a defense force over long periods of time. Players will have to make strategic choices about the capabilities they need and how to use them. A campaign of conquest is possible, but will have impacts that make it hard to sustain indefinitely.

Over time, obsolete units can be updated at the cost of being unavailable in an emergency. The pace and timing of technological upgrades are another factor the player will need to consider. It is likely that the player’s attention to military affairs will wax and wane, leading to cycles of stagnation and renewal that competitors might seek to influence.

Concluding Thoughts

There’s obviously much more that could be said about the combat system - I’ve not gone into any numbers at all, nor covered the inevitable questions of balance. The menu of military capabilities has to cover multiple technological eras without making each level-up a dramatic game-changer, which is a project in and of itself. This is an area where I aim to do more research in the near future; it will strongly impact the development of an AI capable of putting up a challenge.

But I don’t want these weekly pieces to run on too long. In the future I’ll put together some descriptive scenarios to illustrate the challenges Unite the World is meant to put players through, and also fully describe more of the baseline concept for resolving combat terms. Always more to do!

I hope this conveys a broad sense of the general approach, and suggestions from more experienced wargame designers who have spotted pitfalls in this approach are welcome. Software design is an iterative process where no plan survives first contact with reality. But the general aesthetic and mission is important to nail down early on. The player should always feel as if they have a handle on what forces are at their disposal and what they can do. It’s part of the game to discover that mistakes have been made that demand short and long term adaptation.

Thanks for reading - more to come next week. Take care, all!