Unite The World: The Policy System

Simulating the impacts of public policy measures can be elegantly done using a simple card system. Though the Civilization series later jumped on this bandwagon, Fate of the World did it well too.

The third major sub-game that drives Unite the World revolves around politics and policy. I’ve written about the wargame and economic development sides already, so this week I’ll turn to the system that gives players a chance to add some additional character to the experience.

That the US elections were held this past week has nothing to do with the timing, though I suppose it does make the post more topical. However, I have a professional academic background in policy studies, which means that I view politics and policy through a slightly different lens than most.

Policy, as military theorist Clausewitz put it, is war. The full quote using the best translation goes “war is policy continued by other means,” but he was speaking to a general view - still prevalent today - which holds domestic and foreign policy as distinct. While analytically and often practically convenient, setting aside this Western presumption about how the world works reveals their underlying unity.

There is no inherent distinction between what a government does at home and abroad: all action is an expression of intent through the application of resources. Governments are, in a scientific sense, human institutions that offer governance: services which markets or society don’t produce enough of but communities can’t do without. Defense against major external threats is one of them. The flip side, guarding against ones from within, is too. The mechanics are less visibly violent mostly because of the power imbalance between governments and the majority of citizen groups, most of the time.

All governments will deploy some level of violent coercion in the final resort, bound only by whatever incentives drive them - those fostered by good institutions, ideally. The fundamental question of concern is the conditions under which violence can used - and on whose behalf. Politics generates the relevant policy, which is then executed through material action: the application of resources to a distinct end. Scarcity of resources is, in some way, always the root cause of violent escalation, whether in domestic of foreign affairs.

In a resource-limited world, all policy invariably does good for some groups and harm to others. So there is always resistance, and it must be respected, as an independent agent is always capable of escalating. The more that violence can be expressed in the form of stuff like angry words and not physical attacks, the better, under the vast majority of circumstances. Mostly because the more matters escalate, the less predictable and more destructive a conflict often becomes.

Most real-world governance is a constant war against the natural entropy of life. Services like public safety, sewage disposal, and healthcare are universally in demand but under-produced by markets because of the nasty tendency people have of discounting the future. It’s hard to appropriately value one’s own health at the age of twenty, as an example - experience in life is what teaches the value of the absence of suffering. There have to be institutions with a certain level of rigidity to either cope with market failures or regulate conditions so working markets can emerge in the first place.

Governance abroad is no different, save that there are multiple competing sources of it who all have a substantial ability to use organized violence to get their way when in doubt. This creates a need for public security to be expanded to encompass defending against external hazards. Of course, historically, keeping that apparatus under control has proven a challenge, its existence generating a whole other layer of politics to contend with.

Ultimately, Policy is a gigantic machine powered by independent groups locked in constant interaction. That’s why at an abstract level it, like warfare, macroeconomics, and most other systems, can be effectively represented as a game. In the rawest sense, a policy “card” entails a modification of some piece of the underlying systems that power the simulation. These allow a player to make adjustments to certain aspects of the gameplay and experience. Compelling strategic gameplay can be encouraged by attaching costs and benefits to each.

This post will first discuss how this system was implemented extremely well in an educational simulation, Fate of the World, which came out over a decade ago. It was a unique collaboration between non-profit and university groups that allows the player to take on the role of a global leader trying to cope with climate change.

Frankly speaking, anyone who cares about effective climate policy really should play Fate of the World. It’s on Steam for like ten dollars. The learning curve is tough, but there are online guides. If you ever wanted to get a feel for why sustained effective climate action is so difficult, even if you’ve got the very best of intentions, this is the title to play.

For the record, I can usually get about ten billion people living comfortably through the next century and half with every region reaching developed world living standards and global warming kept to around 2.5C past pre-industrial. A lot of vulnerable species don’t survive, it ain’t great for the Amazon, and substantial geoengineering of the atmosphere using sulfates is required, but hey, unlike fair few play-throughs, there’s no regional nuclear war.

And humans even get to go to Mars! Where they soon discover what a silly idea it is to spend months in microgravity soaking up radiation only to sit in a cave not that unlike ones you could find in Arizona. Only there’s no coming home, and you’re watched over by a robot clone of Elon Musk controlled remotely from the comfort of his Earth-bound yacht.

Hey, I’m as pro-space travel as the next space opera fan. I wrote and published a whole space opera trilogy because why not? But before anyone gets too eager to sign up for a trip to Mars, they should probably enlist in their country’s navy and serve in submarines for a few years.

Card Games And Policy Systems

Civilization 6 is a popular enough game that I suspect if anyone reading this is familiar with grand strategy titles, they’ve at least seen a screenshot like the one below. I came to it after a long break from the series, and though the puzzle style of Civ 6 eventually wore on me, I felt that the card game aspect of the society sub-game worked very well.

To implement a card-based system should be straightforward from a coding standpoint, because the essence of each card in a game like this is some kind of variable tweak. If you’re short on money, playing a card that reduces the costs of certain upgrades can be a lifesaver. You can play several of the same type to offset a structural weakness or capitalize on an advantage.

The number of cards available to the player adds a second strategic layer, creating incentives to design a strategy around this consideration. I tend to favor global-level boosts in most games, so I’m always looking to invest in capacity. Civ 6 connects the type of government to the number and type of card slots available, making the choice of running a democracy or a monarchy feel meaningful.

Another useful feature of cards is that patterns of use can be tracked by the game, generating information that can power a categorization algorithm. This in turn allows for countries to self-sort into coalitions predicated upon similarities in policy. By and large, that’s one of the key factors which helps countries associate in the real world.

North Korea and Putin’s russian federation are finding it fairly easy to cooperate right now because their governments share similar characteristics. Israel and the USA have quite a bit in common despite their own differences in size. Most of Europe feels able to work together because when all your neighbors are democracies you’re less likely to be attacked by anyone - so long as you don’t pick fights.

It isn’t that different government types don’t work together - the USA and Saudi Arabia are a perfect case study in that - only that similarities tend to make trust easier. Democracy-autocracy pairings tend to be evidence of latent imperialist tendencies in the former.

Fate of the World is not a competitive game, and unlike Civ 6 the card game is the entire show. In fact, it’s hardly fair to call FotW a game at all: it’s an interactive shell around an extremely powerful global systems model.

Spanning the years 2020 to (depending on the scenario) 2200 in five year increments, FotW lets the player manage a dozen geographic regions from a very high level. The goal is simple: prevent global temperatures from rising too high. Three degrees marks a major tipping point beyond which the damage wrought by climate change swiftly becomes too much for organized society to bear.

Something very remarkable about FotW is that it gives the player almost total freedom to choose what policy measures to take and where. The limits are mostly determined by how much income is received - a simple function of global wealth - with a maximum of six card slots for each region. It costs quite a bit to open one, meaning that the player has to be strategic about where and how they invest.

There are different card decks corresponding to different policy spheres; some focus on human welfare, others environmental quality. Energy, research, and even covert ops are all there. Also included are global options like Tobin taxes applied to financial transactions in richer countries to raise more funds, building out renewable energy, and setting up a headquarters for a Global Environmental Organization that unlocks some major cards like a global Green New Deal and space exploration.

The designers deserve a lot of credit for not automatically nuking (heh) options like actually expanding fossil fuel use. There’s even a scenario where the goal is to raise planetary temperatures by a catastrophic 6C before 2200. Though published by groups that are very determined to fight climate change, the consequences of different paths forward are the player’s to reveal.

What’s more, the underlying models are about as accurate as you can make anything covering such a long period of time - and into the future! Unlike the climate doomers, who insist that unless everyone repents of consumerism tomorrow and embraces the crunchy lifestyle all is lost, actual scientists are looking for ways to mitigate and hopefully reverse the impacts of greenhouse gas pollution. There are, unfortunately, global systems that exhibit so much inertia that it’s going to take a generation to shift them.

As public pushback to climate action mounts worldwide, FotW is highly useful as a simulation that lets the player experiment with different strategies for bringing change in the face of opposition. There are no free lunches in this world, especially when it comes to policy, and if you want to reboot a global economic system to avoid it strangling itself in the long run it’s essential to understand that there are always tradeoffs to consider. Consequences cannot be ignored indefinitely.

FotW forces players to confront the inevitability of resistance. Each region has its own level of inherent stability, and any damage to the economy will swiftly impact the popular mood. Regional populations also differ in both their starting views on climate action and how affected they are by it. It is possible to be kicked out of a region entirely if public support for the GEO drops too far. When that happens, the region does its own thing, usually turning to the cheapest sources of energy and driving up carbon emissions. If you set up a GEO headquarters and lose that region, it’s game over.

Any activist who recommends simple solutions to environmental degradation like everyone giving up meat or buying electric cars really ought to prove they can beat the game before they run their mouths. Go ahead, try it, see what happens!

It’s possible to convince populations to go vegetarian… but it will take a generation, cost a lot, generate resistance to climate action generally, and in the end still have dramatically less impact than switching a single region from coal power to renewables. As for electric cars, they’re wonderful - once the electric grid isn’t burning coal. Now, it’s possible that in net terms a coal plant powering an electric car fleet is better for the environment and climate than everyone using gas engines, but a policymaker still has to consider the tradeoffs. What other cool thing didn’t get funded so electric cars could? Did safeguards against worsening storms or fires not go through? You can build out nuclear power to handle the load, but watch out for uranium depletion… and proliferation, if the political situation gets dicey. If a regional nuclear war breaks out, that’s another early game over.

Thanks to incorporating lots of neat models, FotW ensures that the consequences always emerge. There’s no hidden game master manipulating the experience according to some morality play or an AI cheating just to offer a challenge, only a bunch of variables moving in accordance with their starting state, native potential, and the policy tweaks the player makes. You can use it to test out real world policy trajectories without hand-waving away the harsh reality of never being able to get everyone to agree and some people having to lose.

At one point a sequel to FotW was in development, but I’ve never heard more about it. My strong suspicion is that the climate movement’s embrace of a mostly vibes-based approach in recent years is partly to blame. It has become another religious cult determine to impose its vision of morality on everyone else. Impervious to scientific critique, it has gone down the road of embracing a narrow ideology of climate action over meaningful progress, and for that you don’t need simulation, just sermons.

Sound familiar? It’s the story of the past twenty years of American politics. Feelings over materials. People learn, eventually. Sometimes even remember, for a while.

The primary objective in Fate of the World is minimizing the greenhouse gas emissions that lead to the radiative imbalance slowly heating up the planet. But in a world where it is impossible for any global organization to compel even a minority of the world to behave a certain way, fighting climate change depends on learning how to manage chaos.

An excellent exercise is interacting with real-world models - even if now a bit outdated - which illustrate the challenge of keeping people happy and wealthy enough to tolerate a dramatic retooling of the guts of the global economy. This is something that can never be centrally planned, only managed using indirect instruments. Contrary to the standard government centric mode most conventional public policy operates in, effective global policy has to be able to ride the winds of anarchy.

This is, of course, not a blog about climate policy. I just happen to have studied and even taught it once upon a time. But I am absolutely certain that just as pilots undergo rigorous simulation training, so should every policy professional. The only way to become competent at managing complexity is to fail a lot when it doesn’t really matter. Hence the need for better simulations and worlds.

Policy in Unite the World

Part of the reason that I wrote so much about Fate of the World is that Unite the World’s endgame is inspired by the same fundamental issues. With the endgame being a weak point in most grand strategy titles, degenerating into a player who built enough of an advantage steamrolling the competition, when your own economy starts taking serious hits from climate change and unrest mounts suddenly conquest for the sake of it won’t look that bright.

But even the default scenario is not predominantly about climate change itself, rather the challenge of developing and executing strategy on a dynamic landscape. An advantage of using a province-based map is that each can have whatever attributes attached the designer would like. That means the base game can be widely adapted to suit different objectives.

The policy system can also be extremely flexible. As a given card just modifies some aspect of the underlying model, the options granted to the player depends mostly on avoiding cognitive overwhelm. A common practice is to have cards ranked according to their impact, with bigger ones tied to higher costs. This is intuitive, though if there cards that affect rates of things next to ones covering gross quantities, confusion is inevitable.

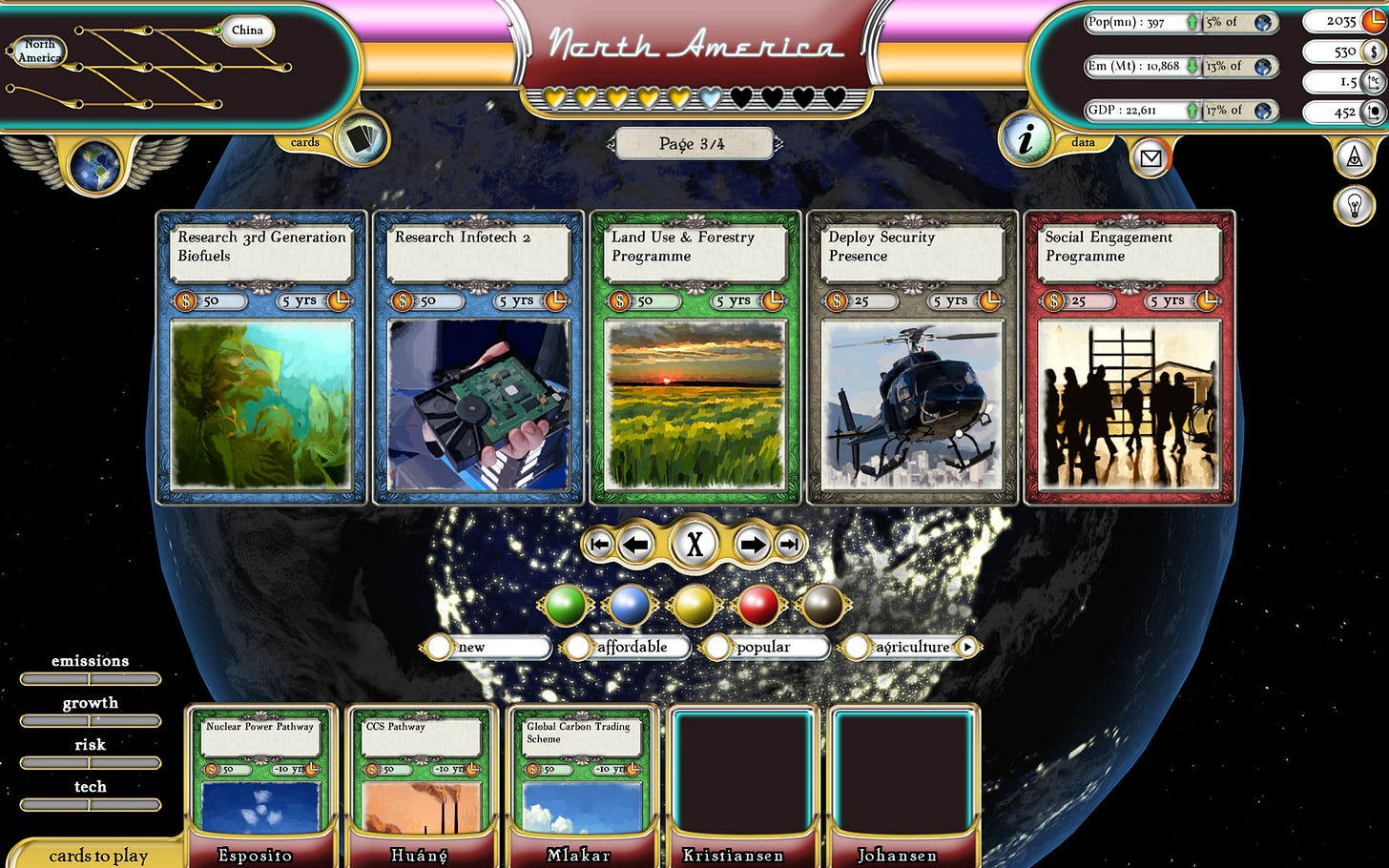

The balance has to be determined through testing, so as is the case with the database of military units Unite the World will eventually need there aren’t specific numbers to work with at this stage. But the following breakdown should give a general sense. Here’s a crude graphic to get a feel for how the policy game might look on a screen:

Economy

These cards allow the player to allocate money to offset issues with scarce resources and inflation. They can mitigate - or reinforce penalties that slow growth or even outright accelerate it further. The consequences of inequality between regions can be reduced. Economic deck cards are also useful for dealing with discontent indirectly - sometimes even directly through financial subsidies.

The tradeoffs with economic growth I’ve covered a lot before - faster is better in some respects, but you’ll either have to take a discontent hit when inflation bites or pay to cope with people’s frustration. It will often be the ability to translate money into boosted production of a scarce resource that will make economic policy helpful at a critical moment.

Society

Population levels are one of the key model parameters, with growth rates tied to international and domestic factors. To control how fast the country levels up in the economic sense, players can use cards that slow population growth rates. The opposite effect is also possible if a player chooses to maintain a given level while making the economy larger.

Boosting population growth will have a negative impact on domestic dissent, but increase the size of the economy in the long run. Decreasing it can make the population happier and even wealthier, but the economy will stagnate. In addition, places that lose population generally resent those that gain it. Many cards in this deck also help compensate indirectly for inequality impacts, as well as the contentment issues impacting social stability.

Military

Naturally, a card deck impacting variables important in the wargame or military development side is included. These can reduce costs, improve efficiency, and generally make combat easier. Accessing military gear beyond the level supported by the country’s economy or even receiving expeditionary forces from allies is made possible by this deck.

Some more general policies will be included that aren’t easily tied to a particular domain.

Though I didn’t go into this in great detail in the wargame brief, one of the crucial factors impacting military performance will be readiness. A newly deployed unit will be inefficient until it gets its footing, making it necessary to keep some deployed to fend off surprise attacks. The rate of improvement and cost of keeping forces in the field are both amenable to policy cards.

Patterns of card employment will be used to characterize the player’s alignment on the global stage, helping to create distinct alliance groupings around human or AI players. Naturally, competition over certain allies raises another point of productive tension.

To give the player more aesthetic control, many cards will have similar effects but incorporate different consequences. A player who wants to simulate aspects of a classical capitalist or communist regime can do so.

Diplomacy in Unite the World is handled through what amounts to an almost identical card-based system, accessed from its own menu and covered under a separate budget. An embassy, once established, can not only be grown but also directed through use of cards to enhance select attributes, like resource production or the rate at which provinces grow trusting enough to become allies and eventually even unify.

Policy measures come into effect at the start of the next year, just like economic development projects. They are allocated a share of the budget, then it’s up to the player to decide the following year’s moves go before they take effect.

This arrangement is intended to pair naturally with the systems that require a little more hands-on management, which is why the diplomatic component is split off. A player will only need to check in with this sub-game periodically, using it to steer the country over the long run while they’re focusing more on other matters.

Conclusion

I’ve actually written more about other games than Unite the World, but I think that’s just a useful illustration of how good techniques spread. As with every aspect of the design I’m laying out in these posts, there is room for improvement.

Together, the wargame, economic development, and policy subgames should combine to offer an intuitive and flexible platform. A future posts will dive into some of the possible ways a scenario could evolve in a sort of hypothetical after-action report to demonstrate how a prototype should look.

I will also be writing about other game design concepts, so not every week will focus on Unite the World. Once I have a good library of concepts laid out, I’ll see what readers want more of. Take care until next Friday!